Dickinson Lab

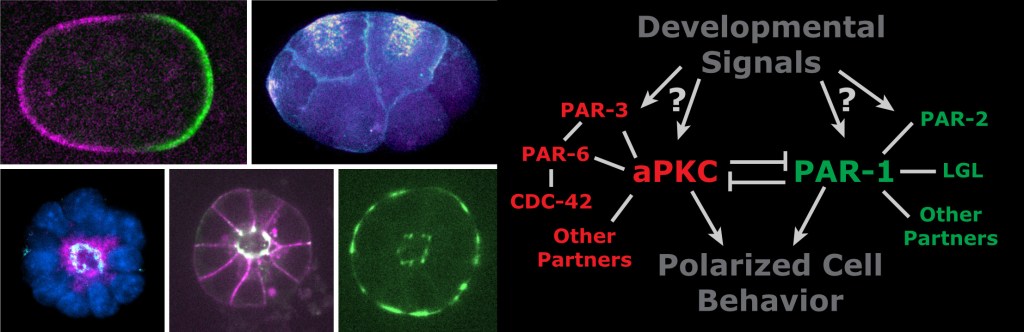

The cells you see here have something in common:

…They are all polarized.

Cell polarity – when two sides of a cell are molecularly distinct – is a basic property of eukaryotic cells. Nearly every cell in your body has to polarize in order to function normally. That includes epithelial cells, neurons, migrating cells, immune cells and dividing stem cells. When polarity is disrupted, disease often results.

Cell polarity is a fascinatingly complex behavior

Conceptually, polarity arises because two groups of proteins localize to opposite ends of a cell and mutually antagonize each others’ binding to the plasma membrane. But what are the biochemical interactions that lead to mutual antagonism? What determines the direction of the polarity axis and the timing of polarity establishment? How do cells coordinate their polarization with neighboring cells or other aspects of their environment? More broadly, how do the signals cells receive in developing embryos inform their behavior? These are the questions we lie awake at night pondering.

A unique, interdisciplinary approach

We study cell polarity using a multidisciplinary approach.

- We do most of our work with a carefully-chosen in vivo model system: the C. elegans embryo, in which multiple different cells polarize in a simple and stereotypical manner in response to known spatial and temporal cues.

- We use high-resolution, quantitative fluorescence microscopy of living cells to study protein dynamics during cell polarization. To avoid expression-level artifacts, we work almost exclusively with proteins tagged at their endogenous loci.

- To gain dynamic information about protein-protein interactions, we use a single-cell biochemistry method that our lab has developed. Briefly, we lyse cells in nanoliter volumes and quantitatively measure protein-protein interactions using single-molecule pull-down.

- We test specific hypotheses by engineering targeted mutations into endogenous genes.